Mount Eden | El Monte Edén

English

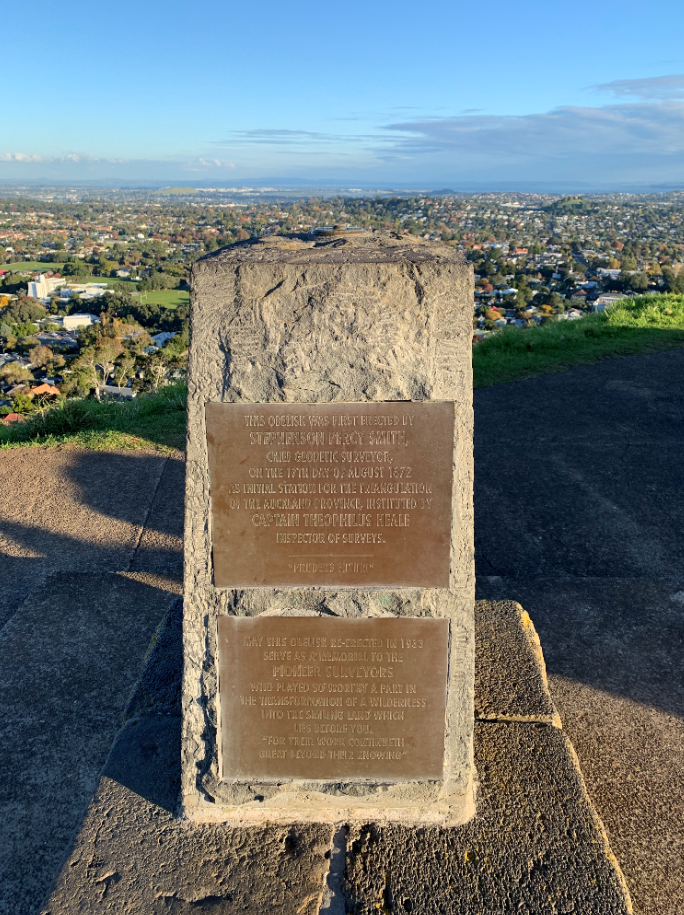

Auckland, the largest city in New Zealand, is an isthmus—a narrow strip of land joining two larger landmasses in the North Island. The tallest point in the city is a dormant volcano commonly known as Mount Eden. Climbing up to the summit, located 196 meters (643 ft) above sea level, is a popular hike. Māori tribes took advantage of this commanding location to build a pā, a fortified defensive settlement with engineered terraces on the hillside that define the landscape to this day. In 2014, a court decision granted ownership of the volcano to the Tamaki Makaurau Collective of 13 Auckland iwi (Māori tribes). The site was officially renamed Maungawhau/Mount Eden and is now co-governed by the Collective and Auckland City Council for the benefit of all the people of Auckland. It was within this context that I started to read about Te Tiriti o Waitangi, or The Treaty of Waitangi. This document, of great importance to Māori and all New Zealanders, was first signed on February 6, 1840 by representatives of the British Crown and Māori from the North Island. The treaty has been highly significant as a political framework between New Zealand's government and Māori. The treaty was signed by more than 500 Māori chiefs, despite reservations. Discrepancies between the English original text and the translation into Māori led to disagreements that culminated in the New Zealand land wars. During the second half of the 19th century, Māori generally lost control of the land that was rightly theirs. In 1975, the Treaty of Waitangi Act was passed establishing the Waitangi Tribunal—a permanent commission of inquiry to interpret the original Treaty, research breaches of the Treaty by the British Crown or its agents, hear claims by Māori iwi, and suggest means of compensation. Monetary settlements totaling more than $1 billion dollars and transfer of ownership of land to iwi have been awarded to various Māori groups, and claims are presented to the Tribunal on an ongoing basis. Māori and pākehā worldviews of land care taking are as different from each other as an active volcano is from one that is dormant. This difference is visible in the profound irony of the statement carved on a plaque that stands on Maungawhau. It says: “May this obelisk re-erected in 1933 serve as a memorial to the Pioneer Surveyors who played so worthy a part in the transformation of a wilderness into the smiling land which lies before you. For their work continueth great beyond their knowing.”

Español

Auckland, la ciudad más grande de Nueva Zelanda, es un istmo, una estrecha franja de tierra que une dos grandes masas territoriales en la Isla Norte. El punto más alto de la ciudad es un volcán inactivo comúnmente conocido como El Monte Edén. Subir a la cumbre, ubicada a 196 metros (643 pies) sobre el nivel del mar, es una caminata popular. Las tribus maoríes aprovecharon esta ubicación dominante para construir un pā, un asentamiento defensivo fortificado con terrazas diseñadas en la ladera que definen el paisaje hasta el día de hoy. En el 2014, una decisión judicial otorgó la propiedad del volcán al Colectivo Tamaki Makaurau de trece iwi (tribus maoríes) de Auckland. El sitio pasó a llamarse oficialmente Maungawhau/Mount Eden y ahora está cogobernado por el Colectivo y el Municipio de Auckland para el beneficio de toda la gente de Auckland. Fue dentro de este contexto que comencé a leer sobre Te Tiriti o Waitangi, o el Tratado de Waitangi. Este documento, de gran importancia para los maoríes y para todos los neozelandeses, fue firmado por primera vez el 6 de febrero de 1840 por representantes de la Corona Británica y los maoríes de la Isla Norte. El tratado ha sido muy significativo como marco político entre el gobierno de Nueva Zelanda y los maoríes. El tratado fue firmado por más de 500 jefes maoríes, a pesar de ciertas reservas. Las discrepancias entre el texto original en inglés y la traducción al maorí llevaron a desacuerdos que culminaron en las Guerras de Nueva Zelanda. Durante la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, los maoríes generalmente perdieron el control de la tierra que les pertenecía. En 1975, se aprobó la Ley del Tratado de Waitangi que estableció el Tribunal de Waitangi, una comisión permanente de investigación para interpretar el Tratado original, investigar las infracciones del Tratado por parte de la Corona Británica o sus agentes, escuchar reclamos de las tribus maoríes y sugerir medios de compensación. Acuerdos monetarios por un total de más de $mil millones de dólares y la transferencia de la tenencia de la tierra a los maoríes han sido otorgados a iwi maoríes, y las demandas se presentan al Tribunal de forma continua. Las cosmovisiones maoríes y pākehā sobre el cuidado de la tierra son tan diferentes entre sí como lo es un volcán activo de uno que está inactivo. Esta diferencia es visible en la profunda ironía de la declaración tallada en una placa sobre un obelisco que se encuentra en Maungawhau. Dice: “Que este obelisco reconstruido en 1933 sirva como un monumento a los Agrimensores Pioneros que jugaron un papel tan valioso en la transformación de un desierto en la tierra sonriente que se encuentra ante ustedes. Porque su trabajo continúa mucho más allá de su conocimiento”.